It had never occurred to me that I would ever be the subject of a lockdown, or how fragile our world was. Up until the last few months I’d always been quite naively optimistic about the inexorable and uninterruptable trajectory of society towards an increasingly better and safer future. I think I just passively and lazily assumed that society and our “systems” (I don’t really know what I mean by that) were extremely resilient and that some people smarter than me would have figured out the solutions for every eventuality. It was probably also partly the result of the optimism bias effect, me simply being unduly optimistic about the prospects of future events. This is probably because it’s less cognitively demanding to worry about the future and have to plan for it and to put the work in for it now. If we really think about it, when we realise that there’s a problem that we’re likely to encounter in the future, by just assuming that it’ll sort itself out somehow, we are essentially offloading the work to our future selves, who will probably be less able to deal with the problem than we are right now, simply as a function of having less time available. Sort of like paying for something with your credit card. Eventually you have to pay the bill. Not that there’s much that I could really have done to prepare for this situation that we find ourselves in right now. Maybe I could have stocked-up on some hand sanitiser, or anticipated that getting to the front of the supermarket delivery queue would have been prudent. But apart from that, in this case there’s not much that worrying about the issue would have done to benefit me, apart from maybe feeling a sense of vindication after having spent years on the street with a cardboard sign saying “the end is nigh”.

It is crazy though how much society has been upended by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (I’m a scientist, so I like to use the technical name, just personal preference, not a big deal). It’s even crazier when we consider that it’s not even that lethal a virus. However, where it lacks in lethality it apparently more than makes up for in transmissibility. The low death rate can mistakenly give credence to the words of those who say that this is all an overreaction. Because of its transmissibility, although it may not be an efficient killer, it maximises its exposure, which increases its total mortality toll, just through a simple numbers game.

Those who call the near-universal government measures excessive and an overreaction invariably cite the damage to the economy that this shutdown has caused, or the supposedly unnecessary restrictions that have been imposed on low-risk individuals. And it is here where we see lack of nuanced understanding of the subject, the range of relative value that people place on human life, and the moral dilemmas that governments are entrusted to deal with on a regular basis, but this time magnified to a far greater degree. After all, the essence of politics is compromise and trade-offs, and tough calls between choices that, in a perfect world, wouldn’t need to be choices at all. This is the arena of population ethics, where politicians decide on a grand and abstract scale who and how many people are worth saving, and it happens on a far more regular basis than we do or are willing to realise.

Is the sustenance, protection and prolongation of human life the number one goal of governments? Possibly, and hopefully most likely. But is it their all-consuming goal? Of course not, there are other things that governments need to invest in, such as education, infrastructure and ensuring that people have a quality of life. By not investing all resources into public health (physical and medical, at least) and public safety, governments are necessarily increasing the risk of diminishing those things. But we wouldn’t accuse them of being monsters for this, because we all understand that there is a degree of acceptable risk involved in living, and that a good life is not one where one stays inside for its duration. We all take risk in our daily lives, and we determine what level it is acceptable. When it comes to things that involve almost exclusively personal risk, then this is usually left to the individual to determine and decide for themselves, except in cases such as illegal drugs, for example. But you’re free to go freesolo rock climbing if you want, you’re free to play American Football, you’re free to skateboard, and you’re free to sun yourself until you resemble an oxidised Peperami©. These things usually only present a risk to the individual themselves (except in cases where several parties are aware of and consent to the risk, and the risk doesn’t extend beyond themselves, such as aforementioned gridiron) and so there is no law against partaking in them. The government typically only regulates against activities that pose a significant and direct risk to others. This is based on John Stuart Mill’s famous Harm Principle.

The complications arise, however, when the activities that pose such a risk to others is simply walking outside your front door, or things seemingly as innocuous as meeting-up with friends or getting a coffee, or even going to work. Activities that are so basic and fundamental to our society and way of life that have now been prohibited to an unprecedented degree. Not necessarily only because the activities pose a significant risk to the individual performing them, or even that the collective consequence of these risks would be too burdensome for the healthcare systems to deal with, but also largely because of the risk that these activities pose to others who are more susceptible to suffering severe symptoms as a result of the virus, exacerbated to a great degree by how easily the virus is spread and how delayed the feedback is, due to the incubation period. This really is a unique situation as a direct result of the nature of the virus and it has sent society into shutdown and forced extraordinary measures to be taken.

But clearly society needs to retain its capacity to function and serve its population. People need to be able to have shelter and pay the bills and have food to eat, and in order to do this they need currency. If people are being told by the highest authority that they should not go to work, how are they expected to earn money to support their lives and the lives of their families? Well, as we are seeing, governments are rolling out huge welfare budgets to support families and individuals during this time in order to keep society somewhat afloat. But for how long is this sustainable? And if there is a short lifespan on this solution, what do we do beyond that? Which side of the coin do we bow to? Do we risk an economic depression or do we risk the death of thousands of people?

In order for us to make some headway on this question, we need to know the numbers, or at least have a rough idea of what the numbers might be. I’m not an economist so I can’t predict what the economic effects might be or what the solutions might look like, so let’s instead look at the coronavirus-related numbers regarding mortality and infection.

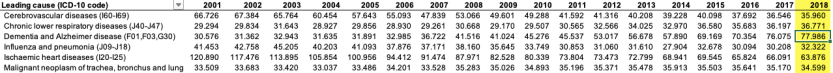

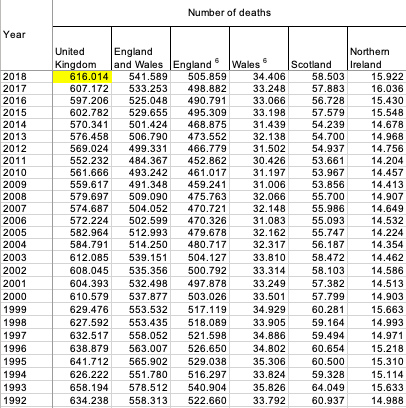

The question that we need to ask is: what is too many lives and what is an acceptable death toll? Let’s look for a moment at the United Kingdom as a case study and compare the current coronavirus deaths toll to the biggest killers in 2018. So, in 2018, the biggest killer of people in the United Kingdom was Alzheimers disease and dementia, with 77,986 deaths, and the lowest in the top 6 being influenza and pneumonia, with 32,222 (which is without social distancing and self-isolation measures).

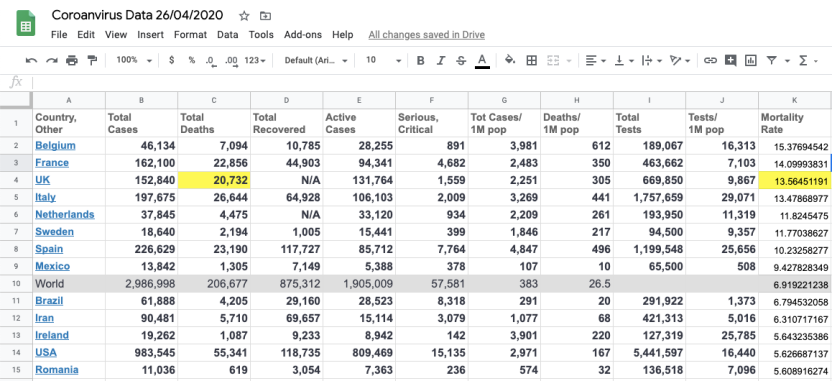

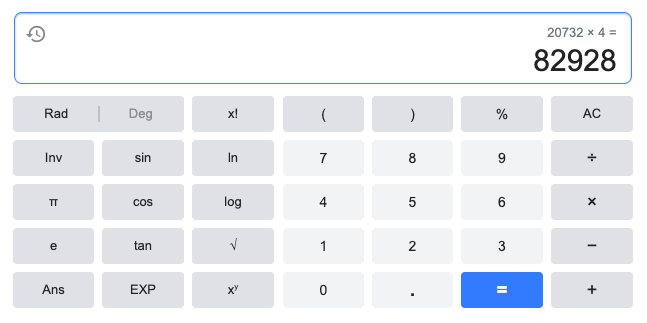

According to Worldometer, as of writing this post, the UK has suffered 20,732 deaths as a result of the coronavirus. And this is within a time frame of approximately five months, with approximately two months of that being during a lockdown, and infection rate likely being very low at the initial stages. What would the total mortality have been over the course of a year had there been no lock-down enforced? Where would it have ranked compared to the other causes of mortality? I won’t speculate, but if we simply multiply 20,732 by four, assuming that the coronavirus has only really been prevalent in the UK for the last three months, then we get a figure of around 82,928. This gives us a figure that is already higher than the cause of death in the UK, annually, and this estimate is contingent upon conditions of self-isolation and social-distancing.

But let’s try to be a bit more precise about this. Of course, there are many claims that the infection rate is likely much higher than the official numbers, due to the fact that many people are likely to have contracted the virus and experienced few or no symptoms, and are therefore not known to the healthcare authorities. Now, this is highly likely, as coronavirus symptoms manifest themselves on a broad spectrum, so let’s allow that and try to find the possible range within which the true mortality rate is likely to fall.

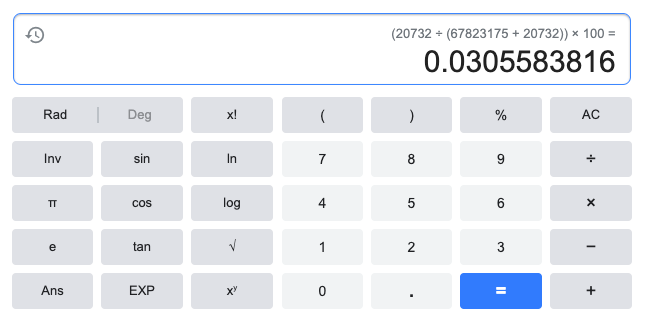

Let’s say then, hypothetically speaking, that the entire population of the UK has now contracted the virus, and that the numbers that appear above are the final death toll. If we assume this, then this is the best-case scenario (assuming that people cannot be reinfected). So if we take the death toll and divide that by the population of the United Kingdom (plus the death toll, to get roughly the original population size) and then multiply the result by 100, that gives us the best possible mortality rate, which is roughly 0.03%.

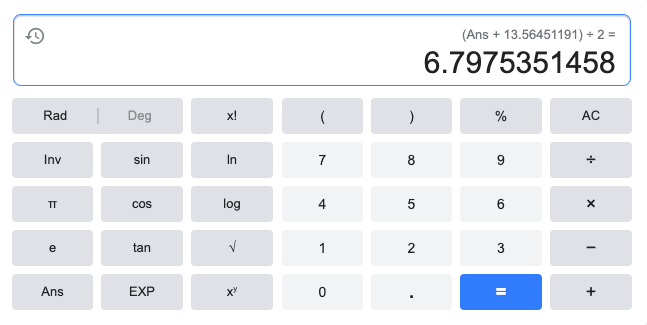

The worst-case mortality rate is then the current official mortality rate (assuming that the current infected population is a perfectly representative sample of the United Kingdom, which is a highly dubious assumption, but for the sake of simplicity, let’s assume it), because we know how many people have died as a result of it with quite a high level of accuracy, but we don’t know with a high level of accuracy how many people have been infected, as was explained earlier, but the true infection rate can only be higher, not lower, because we can’t have false-positive tests. The official mortality rate is, according to Worldometer, 13.56%. So, with there being no reliable way that I’m aware of of knowing what the exact infection rate is, let’s simply split the difference between the two rates. If we take both rates and find their average, then we get about a 6.8% mortality rate.

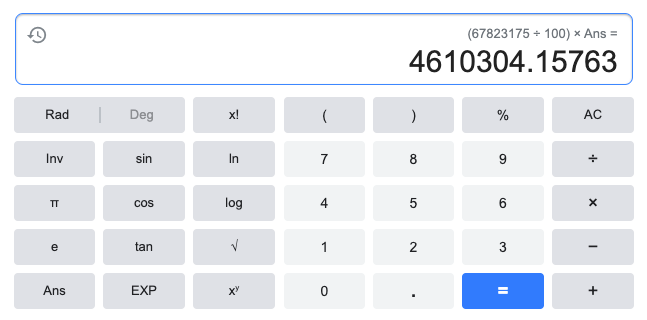

Finally, if we assume that this is the true mortality rate – making the reasonable assumption that that there is a high probability that the number of cases is far higher than official numbers show – and that the entirety of the UK population will eventually contract the virus if restrictions are eased and a vaccine is not developed within that time, then the number of people that will die as a result of the coronavirus (if we don’t develop an effective treatment to alleviate symptoms), based on these numbers (which are, I will readily admit, merely the product of my own logic), will be 4,610,304.

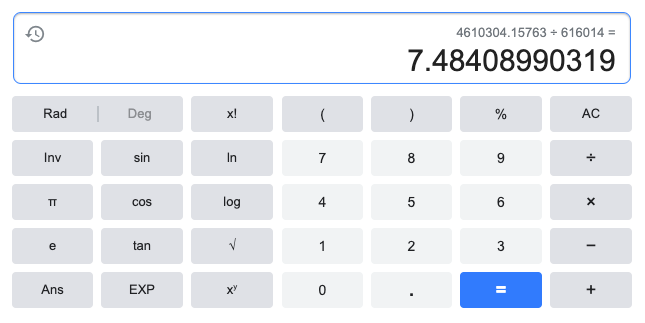

To put this into perspective, the number of people that died in the entire United Kingdom in the year 2018 was 616,014.

That’s 7.5 times less than the projected deaths from coronavirus, which could conceivably occur in less than a year, given the rate of infection, in the absence of social restrictions and a vaccine.

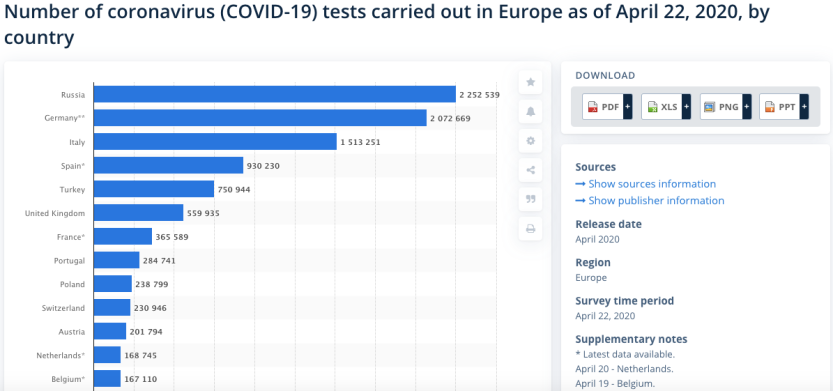

Let’s try to work it out another way though, for a different perspective. The latest data that we have available concerning the number of tests that have been carried out by the UK is from the 22nd of April. The total number of tests conducted up to that date was 559,935.

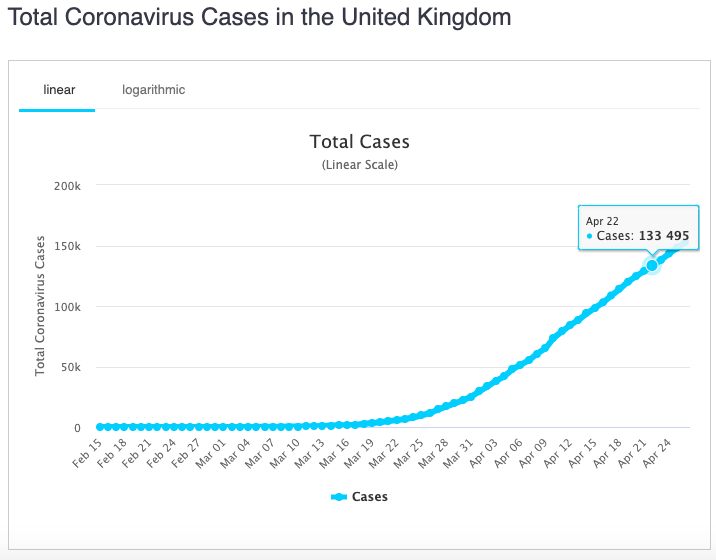

The number of positive cases from those tests was 133,495.

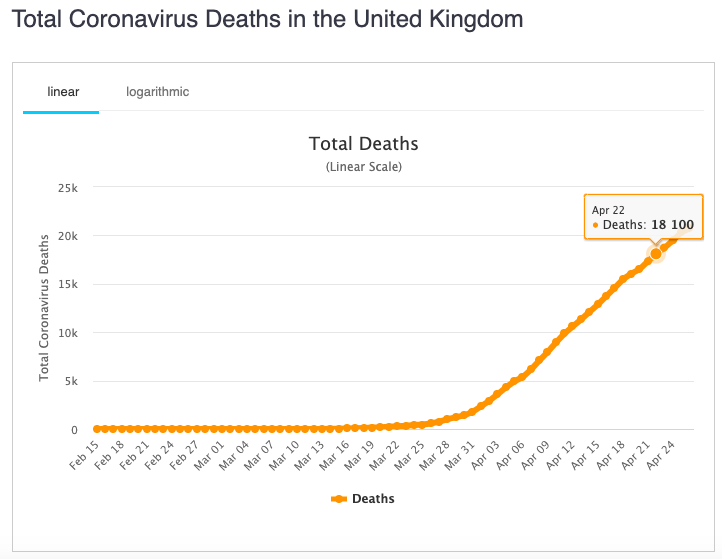

And the total number of deaths was 18,100.

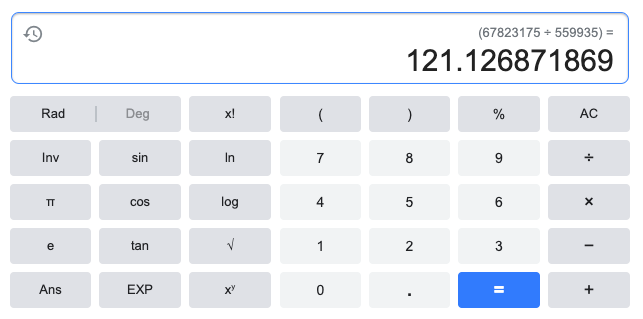

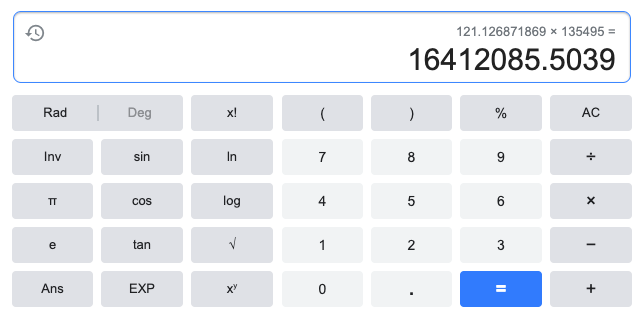

So, again, assuming that this sample of the population that has been tested is perfectly representative (which, again, is a highly dubious assumption), then we can extrapolate the numbers to find the total infection rate within the entire population of the entire United Kingdom at this date. Firstly, we need to find out what fraction of the UK population has already been tested. So, using the population figure used previously in this post, we divide that by the number of tests that have already been conducted, which gives us about 121. This means that 1 out of every 121 people has been tested.

Then, we multiply the number of positive cases by this number, which gives us 16,412,085 potentially infected people in the UK so far.

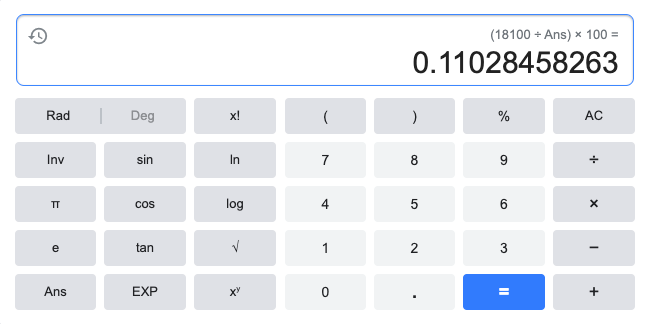

Now, if we take the number of coronavirus-related deaths at that point, divide it by the total number potentially infected, this will give us the potential true mortality rate, which would be 0.11%.

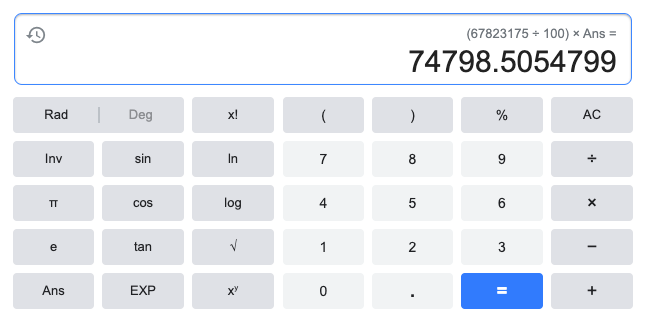

Finally, if we apply this rate to the entire population, we get a figure of roughly 74,799 total deaths, which is a little over three thousand less people than the leading cause of death in the UK in 2018. This number is obviously far more optimistic, then, than the previously calculated figure of 4,610,304, but still socially traumatic. But this number is also contingent on the continuation of the current self-isolation and social-distancing measures.

Whichever number you look at, it’s clear, based on these estimates, that the coronavirus is a public health emergency. So how much is this potential loss of life worth? How do we quantify it? Can we in good conscience allow a loss of life on this scale? Of course, it depends on which numbers that you believe are more likely or reliable and how you weigh the loss of life against damage to the economy and thus the livelihood and quality of life of individuals.

What would be an unacceptable loss of life? And when we decide what this is, and it turns out that this number is likely, then what are the solutions? Surely the only solution in the case of a number that is in the higher end of the range is a complete overhaul of the way society is structured. And how would that society look? If current preventative measures are any indicator of what is required to stymie the spread, then strict social distancing measures will need to be continued and working arrangements substantially altered until a vaccine is developed, something that is unlikely to be available until next year. If at the lower-end then we can more-than-likely simply isolate those most at risk and keep them quarantined until we find a vaccine or some effective treatment.

However, this is all conjecture. I’m not a statistician or a mathematician, or an epidemiologist. I’m just a guy, with a laptop and too much time on his hands. There is really no sure-fire way of telling how many people have been infected by the virus, considering that no test has yet been developed that can tell us whether a patient has had the virus previously, except in severe cases. It could certainly be that many, many more people have contracted it than we think. The likelihood of this, however, is fairly low considering the social distancing measures that have been put in place for the explicit purpose of preventing the spread of the virus.

It’s my opinion that the coronavirus poses a very real threat to the very fabric of our society, and it has thrown into sharp relief the moral question of how we should, as a society, value human life. The powers that be need to evaluate this problem with a skeptical eye, err on the side of caution and plan for the worst, even if not only for this virus but for any future virus that might be even worse than the one that we are currently battling. It is incumbent on governments and major institutions to drastically reconsider the fundamental nature of our economy and how it works. A more transparent and frank conversation must be had with the people about the severity of the stakes. People of course want to work and interact with other people and return to normality, but I think it might be naive and complacent to think that we can slide back into our everyday lives so soon. Generations are defined by their attitudes towards the future and the sacrifices they made for the most vulnerable and those who will inherit the society that they created. Desperate times call for desperate measures, and necessity is the mother of invention. The world is a different place now and all of the assumptions that we have had about how work and life looks like must be questioned. Civil liberties of course need to be maintained and protected, but the question of how we balance this with the clear need to prevent mass casualties on an unprecedented scale is one that I am not qualified to answer. I just hope that people out there who are smarter than me will be able to figure it out, somehow.